I'm just summing up the information readily available elsewhere (if you are willing to wade through endless online debates and the numerous in-depth articles), for people who just want to know right here and now what the best level is to record into their digital audio systems.

So I'm going to start with just a quick easy rule of thumb for these people, followed with a little bit more detail after that to explain why I'm recommending these numbers.

I apologize for simplifying some of the math - but if you're really interested there are plenty of texts and in-depth articles available with a bit of searching. I've included a few references and links at the end of the article.

The rule of digital thumb

- Record at 24-bit rather than 16-bit.

- Aim to get your recording levels on a track averaging about -18dBFS. It doesn't really matter if this average floats down as low as, for example -21dBFS or up to -15dBFS.

- Avoid any peaks going higher than -6dBFS.

That's it. Your mixes will sound fuller, fatter, more dynamic, and punchier than if you follow the "as loud as possible without clipping" rule.

For newbies - dBFS means "deciBels Full Scale". The maximum digital level is 0dBFS over which you get nasty digital clipping, and levels are stated in how many dB below that maximum level you are.

Average level is very important - people hear volume based on the average level rather than peak. Use a level meter that shows both peak and average/RMS levels. Even better if you can find a meter that uses the K-system scale.

Some common questions:

Q: Why do we avoid going higher than -6dB on peaks? Surely we can go right up to 0dBFS?

Answer 1 - the analogue side.

Part of the problem is getting a clean signal out of your analogue-to-digital converter. Unless you have a very expensive professional audio interface, or you like the sound of the distortion that it makes when you drive it hard, then you're going to get some non-linearities (ie distortion) happening at higher levels, often relating to power supply limitations and slew rates.

Most interfaces are calibrated to give around -18dBFS/-20dBFS when you send 0VU from a mixing desk to their line-ins. This is the optimum level!

-18dBFS is the standard European (EBU) reference level for 24-bit audio and it's -20dBFS in the States (SMPTE).

Answer 2 - the digital side.

Inter-sample and conversion errors. If all we were ever doing is mixing levels of digital signals, we would probably be fine most of the time going up close to 0dBFS, as most DAWs can easily and cleanly mix umpteen tracks at 0dBFS.

EXCEPT there are some odd things that happen;

- Inter-sample errors can create a "phantom" peak that exceeds 0dBFS on analogue playback.

- When plug-ins are inserted they can potentially cause internal bus overloads. These can build-up some unpleasant artifacts to the audio as you add more plug-ins as your mix progresses. They can also potentially generate internal peaks of up to 6dB - even if you're CUTTING frequencies with an EQ, for example.

- Digital level meters on channel strips seldom show the true level - they don't usually look at every single sample that comes through. It's possible to have levels up to 3dB higher than are displayed on the meters.

Q: Aren't we losing some of our dynamic range if we record lower? Aren't we getting more digital quantization distortion because we're closer to the noise floor?

Short answer. No.

Really, both of these questions sort of miss the point, as we shouldn't be boosting our audio up to higher levels and then turning it down again. So there's nothing to be "lost".

It's the equivalent of boosting the gain right up on a mixing desk while having the fader down really low, giving you extra noise and distortion that you didn't even need. You should leave the fader at it's reference point and add just enough gain to give you the correct audio level. This is what we're trying to do when recording our digital audio as well - nicely optimizing our "gain chain".

The best way to illustrate this is to throw a few numbers up;

Each bit in digital audio equates to approximately 6dB.

So 16-bit audio has a dynamic range of 96dB.

24-bit audio has a range of 144dB.

With me so far? Probably doesn't mean a lot just yet.

Now, let's look at the analogue side where it becomes slightly more interesting.

The theoretical maximum signal-to-noise ratio in an analogue system is around 130dB.

Being awesomely observant, you picked up immediately that this is a lot less than 24-bit's 144dB range!

In fact, the best analogue-to-digital converters you can buy are lucky to even approach 118dB signal-to-noise ratio never mind 144dB.

So - let's think about this.

If we aim to record at -18dBFS, how many bits does that give us?

24 bits minus 3 (each bit is 6dB remember). That's 21 bits left.

What's the dynamic range of 21 bits? 126dB

What's the dynamic range of your analogue-t0-digital converter again? 120dB-ish.

Less than 20 bits.

One bit less than our 21-bit -18dBFS level.

The conclusion is that when recording at -18dBFS you are already recording at least one bit's worth of the noise floor/quantization error, and if you actually turn your recording levels up towards 0dBFS, all you're really doing is turning up the noise with your signal.

And most likely getting unnecessary distortion and quantisation artifacts.

Apart from liking the sound of your converter clipping, there's NO technical or aesthetic advantage to recording any louder than about -18 or -20dBFS. Ta-Da!

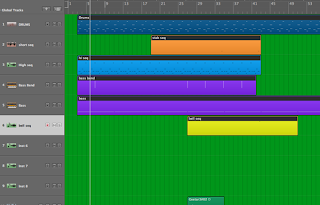

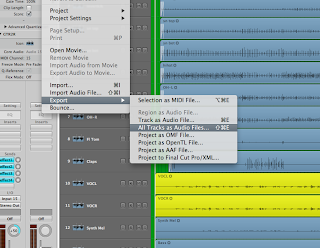

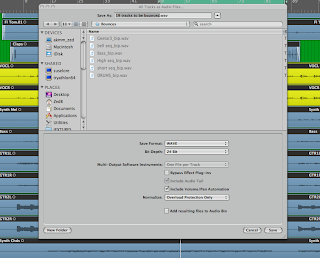

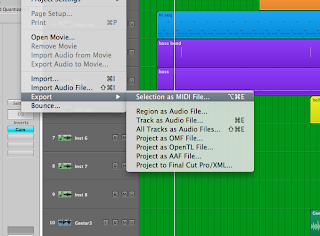

Mix Levels

If you've been good and recorded all your tracks at the levels I recommended, you probably won't have any issues at all with mix levels.

The main thing is to make sure your mix bus isn't clipping when you bounce it down.

Most DAW's can easily handle the summing of all the levels involved, even if channels are peaking above 0dBFS. In fact even if the master fader is going over 0dBFS, there's generally not a problem until it reaches the analogue world again, or when the mix is being bounced down.

Most DAWs have headroom in the order of 1500-2500dB "inside the box". You can usually just pull the master fader down to stop the master bus clipping.

Saying that, it's still safer if you keep your levels under control.

Like I mentioned before - a key problem is overloads before and between plug-ins. If your channel or master level is running hot and you insert a plug-in, it could be instantly overloading the input of the plug-in depending on whether the plug-in is pre-or-post the fader. So use your ears and make sure you're not getting distortion or weird things happening on a track when you insert and tweak plug-ins.

Try to use some sort of average/RMS metering, and try to keep your average mix level between about -12 to -20dBFS, with peaks under -3dBFS.

Mastering will easily take care of the final level tweaks.

To conclude - when recording at 24-bit, there is a much higher possibility of ruining a mix through running levels too high than having your levels too low and noisy.

As Bob Katz says, if your mix isn't loud enough - just turn the monitor level up!

PS - just say "no" to normalizing. That's almot as bad as recording too loud.

References:

Bob Katz' web site.

Plus Bob's excellent book "Mastering Audio - the Art and the Science".

Paul Frindle et al on GearSlutz.com

A nice paper on inter-sample errors

Download a free SSL inter-sample meter (includes a nice diagram of inter-sample error )