Key points

- mp3 is generally MPEG 1 (layer 3). They did extend it slightly in MPEG 2 to add some lower sample rates and some different channel formats.

- AAC (Advanced Audio Coding) is MPEG 2 and also in MPEG 4.

- mp3 only uses 576 blocks to encode audio.

- AAC uses 960 or 1024 blocks to encode audio.

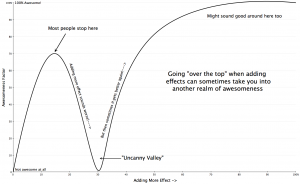

There's a huge difference in quality between the formats - mainly because they tweaked the hell out of the encoding algorithm after the original mp3, so 128kbps AAC sounds almost like CD-quality, whereas mp3 128kbps sounds phasey and dull.

AAC is also what's generally used nowadays for radio broadcast - they call it MP2 though, to confuse the production people.

So what about MPEG 3 and 4 then?

MPEG 3 only had a couple of tweaks to add to the standard, so rather than having a completely new standard, they just updated good ol' MPEG 2 instead. They added things like more channels for surround-sound files and the like.

MPEG 4 was mainly about metadata (information embedded in the files) and even more channels - basically bundling a variety of video and audio formats (and other stuff like subtitles) into a handy container called "MP4".

If there's only audio inside it, it gets called M4A. Though some M4A files can also contain Apple Lossless format at master quality, but at a larger file size. Lossless formats are more like zip files - they're compressed down to smaller size (not as small as mp3 or AAC) but can be expanded again without any loss.

What's this bit-rate thing?

Since most of these lossy formats were designed to be streamed - either on the internet or off an optical disc, they're measured in how many bits per second they need.

Is that the same as sample-rate?

No - mp3s and AAC files still retain the original sample-rate and bit-depth as the original file. At lower bitrates, obviously more information needs to be trimmed out of the audio to make it smaller - hence the quality loss.

So why do we still use mp3 rather than AAC?

Well, if you're using Apple products, you're likely using AAC way more than you know. Otherwise, mp3 has just been around longer and more software can be guaranteed to play mp3s than AAC (although it's pretty rare that something can't play both now). It's like the old VHS vs Betamax video tape format thing all over again - the lowest common denominator (and cheapest format) usually wins against quality.

So what should you use?

If there's a choice - go with AAC. If not, go with mp3. Simple.

(Or a lossless format if possible!)